Modelling business logic like a pro - Spring State Machine

java tech spring

6 minutes read

When it comes to modelling business logic and processes within any kind of application I think it is safe to say - it’s not easy.

And why should it be?

Often establishing what functionalities we need or translating unclear client’s desires into rigid rules is already half of the success. Some may protest since usually there is still no coding involved during this part of project. The thing is that due to the intrinsic nature of any developer’s work, at some point in your career you will for sure face the beauty and complexity of building something from scratch. Valuable lesson that comes with such an experience is that it’s usually easier to model something in a proper way at the beginning of the project than to rewrite everything after some time when you see that your project is on the verge of exploding. 💥

Since we already know that creating a good business model and putting it to life with code is not a trivial task, we may as well take advantage of existing solutions that are trying to ease the pain of defining, setting up and maintaining scalable applications. Fortunately, for any Java developers who use Spring framework, such a tool exists. In this post I want to bring some more attention to Spring State Machine and the perks of using it.

States, states everywhere

First of all it is vital to establish some ground knowledge. State is the fundamental building block of Spring State Framework. You can essentially treat state as a stage in the lifecycle of your project. To give you an example of states in different projects:

- order in an online shop - Created, Packed, Shipped, Cancelled, Delivered

- deal in a company - Initiated, Discussed, Signed, Completed

- meal at the restaurant - Ordered, Prepared, Completed, Served, Paid

and so on. You get the idea. The possibilities are countless and in many projects you are able to extract those states from the product lifecycle. Once you have the whole state pallete at your hand you can proceed to the next level and design a state machine.

How does it work? Basically you need to ask yourself two questions:

- How does a transition from one state into another occur?

- When a transition between two particular states can’t occur?

Answering the first question will result in defining a list of possible transitions within your application. The answer to the second question results in defining all limits to your logic. To give you an example based on the online shop project:

- an order can transition from Packed to Shipped upon calling the method

ship() - an order cannot transition from Created to Packed without

clientPaid == true

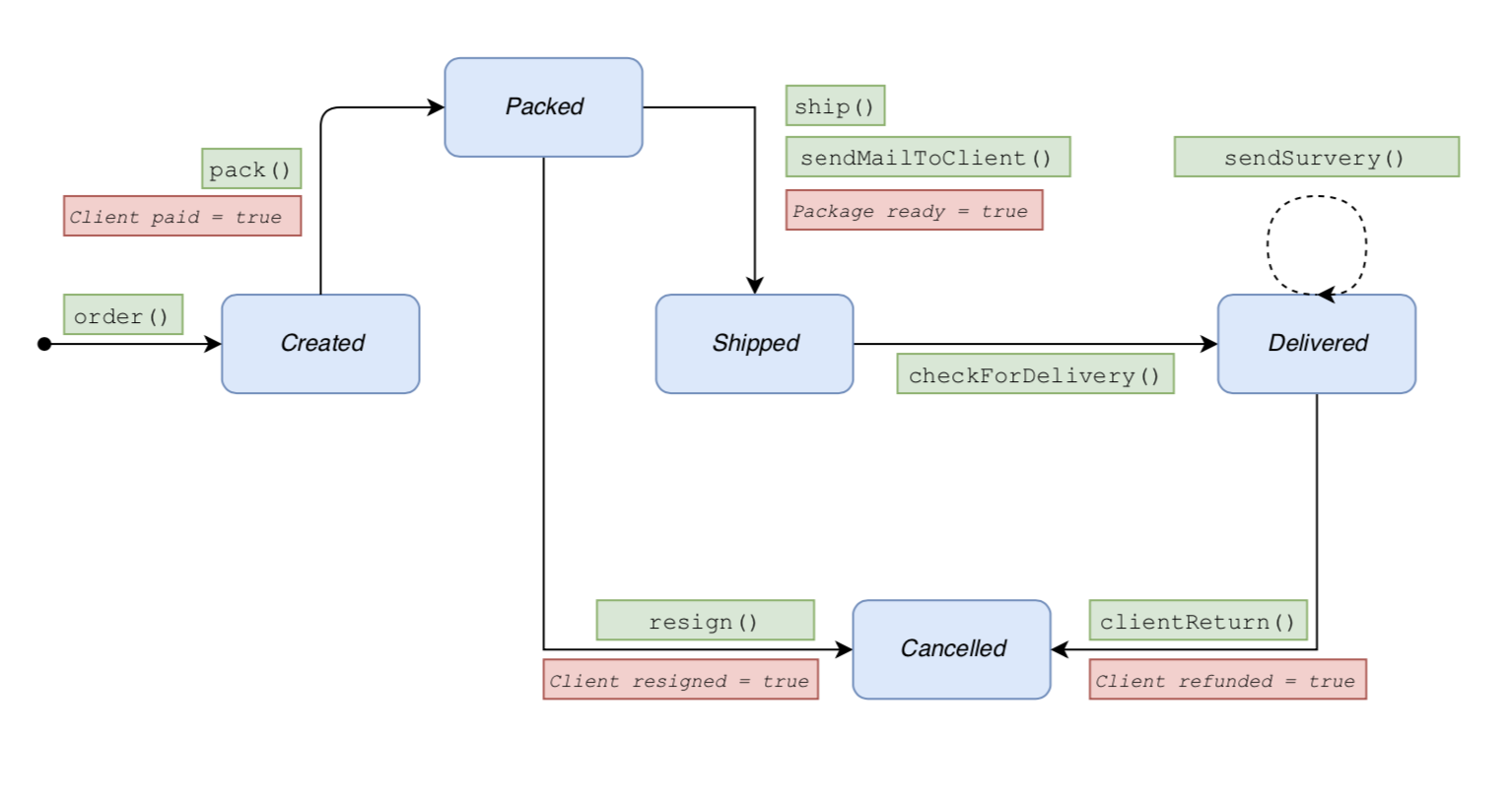

State Machine defines the whole and complete logic of your application. Once you have all your states, transitions and limits established it will be handy to create a graph depicting it. It will certainly look fancy and once all other developers see it, you will be granted the mythical Great Architect badge at your company. As an example how the diagram presents, take a look at this simple visualization of the online shop project:

The green boxes are our transition methods. They show which specific action needs to be invoked in order for the state to make the transition. The red boxes are our limitations showing when can an action occur. It is clear that the package cannot be packed without the client paying for the stuff. The arrows precisely show where the transitions between states can occur. Notice that a transition can take a place within one state. Example: when the package is Delivered, we can send the survey link to the client in order to obtain his feedback regarding the whole buying process. This particular mail won’t change the state of the package but can occur only if we are already in Delivered state. Obviously any given online shop is much more complicated and within all the states there might be a ton of different actions, but this graph gives you an idea of how it should look.

The green boxes are our transition methods. They show which specific action needs to be invoked in order for the state to make the transition. The red boxes are our limitations showing when can an action occur. It is clear that the package cannot be packed without the client paying for the stuff. The arrows precisely show where the transitions between states can occur. Notice that a transition can take a place within one state. Example: when the package is Delivered, we can send the survey link to the client in order to obtain his feedback regarding the whole buying process. This particular mail won’t change the state of the package but can occur only if we are already in Delivered state. Obviously any given online shop is much more complicated and within all the states there might be a ton of different actions, but this graph gives you an idea of how it should look.

Ok ok, but why?

If you are still not convinced by fancy diagrams here are a couple of arguments which might speak to you:

- no more hard coding conditions - by defining state and transitions you rid yourself of those pesky if’s

- easy track of the current app’s condition - because of a finite number of states and transitions it is relatively easy to find why our application is in a particular state

- focus on logic - after the state machine is configured, developers can just concentrate on defining actions and guards, which means you focus more on the actual logic of your application

- preventing out of order operations - thanks to defined actions and guards it’s impossible to move from one state to another without clearly specyfing the transition

- concise business logic - just by looking at state diagram anyone can explain how you application really works

Spring to the rescue

Now that we know the basic logic behind creating a state machine, let’s leverage Spring State Machine and

introduce this idea into our code. For the purpose of this article I will be working with a simple application which

depicts online shop and order handling. The project is based on Java 8 and Spring Boot. The build tool in this case is Maven. There is going to be quite a lot of code so hang tight!

We start by adding the dependency in our pom.xml:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.statemachine</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-statemachine-core</artifactId>

<version>2.0.2.RELEASE</version>

</dependency>The next step is to define all the states within our application. Our states should match the state machine definition. Our online shop main domain would be an Order. Let’s put all of possible states into enum class:

@AllArgsConstructor

@Getter

public enum OrderState {

CREATED,

PACKED,

SHIPPED,

DELIVERED,

CANCELLED,

}Once we have all of our states defined it is also necessary to define all transitions. We need to translate arrows from our state machine diagram into code which means that we need an enum with all possible actions:

@AllArgsConstructor

@Getter

public enum OrderEvent {

SHIP,

PACK,

RESIGN,

CHECK_FOR_DELIVERY,

SEND_SURVEY,

CLIENT_RETURN

}Next comes the most important step, configuring the state machine itself. For this we need to create a class OrderStateMachine.

First lets look at the code and then I will provide all the answers.

@Configuration

@EnableStateMachine

public class OrderStateMachine extends StateMachineConfigurerAdapter<OrderState, OrderEvent>{

@Override

public void configure(StateMachineStateConfigurer<OrderState, OrderEvents> states) throws Exception {

states

.withStates()

.initial(OrderState.CREATED)

.states(EnumSet.allOf(OrderState.class));

}

@Override

public void configure(StateMachineTransitionConfigurer<OrderState, OrderEvent> transitions) throws Exception {

transitions

.withExternal()

.source(OrderState.CREATED)

.target(OrderState.PACKED)

.event(OrderEvent.PACK)

.action(packAction)

.guard(packAction)

.and()

.withExternal()

.source(OrderState.PACKED)

.target(OrderState.SHIPPED)

.event(OrderEvent.SHIP)

.action(shipAction, sendMailToClientAction)

.guard(shipAction)

.and()

.withExternal()

.source(OrderState.SHIPPED)

.target(OrderState.DELIVERED)

.event(OrderEvent.CHECK_FOR_DELIVERY)

.action(checkDeliveryAction)

.and()

.withExternal()

.source(OrderState.DELIVERED)

.target(OrderState.CANCELLED)

.event(OrderEvent.CLIENT_RETURN)

.action(clientReturnAction)

.guard(clientReturnAction)

.and()

.withExternal()

.source(OrderState.PACKED)

.target(OrderState.CANCELLED)

.event(OrderEvent.RESIGN)

.action(clientResignAction)

.guard(clientResignAction)

.and()

.withInternal()

.source(OrderState.DELIVERED)

.event(OrderEvent.SEND_SURVEY)

.action(sendSurveyAction)

.guard(sendSurveyAction)

}

}We need to mark the class with an annotation @Configuration to be loaded by a Spring context. The annotation @EnableStateMachine tells the context that an instance of a state machine can be built and started immediately on application startup. All of the states from OrderState class must be added using a configuration method. The start and end states are optional and can be omitted but in my case I want to set the newly created Order to Created. Next configuration method is responsible for building all transitions and marking all corresponding triggering events. Notice that every external transition needs a source and target event, while internal (like sending survey to clients) is not changing machine’s state. For every transition we need to indicate an action which should occur. Defining a guard means that in order for a transition to succeed it needs to be within application limits, like packing a package only if client paid for the initial order.

Last task is to implement every action we defined in our model and delegate functionalities to proper services.

As an example PackAction.java handles both the action and the guard by execute and evaluate methods:

@Override

public void execute(StateContext<OrderState, OrderEvent> context) {

Order order = OrderStateMachineMessageExtractor.extract(context.getMessage());

orderService.pack(order);

}

@Override

public boolean evaluate(StateContext<OrderState, OrderEvent> context) {

Order order = extract(context.getMessage());

// To perform the pack action, the order must be paid

if (order.hasBeenPaid()) {

return true;

}

context.getStateMachine().setStateMachineError(

new OrderWorkflowException("An order that hasn't been paid cannot be packed"));

return false;

}And that’s it! You have defined the whole logic of the application using states, transitions, actions and guards. If you like the idea, try to put it into life during your next project. To find out more about this framework please visit the official documentation.